At the moment it is common to see the partisan state of its politics as a major problem for American democracy. A picture is painted of the Republican and the Democratic parties retreating behind increasingly high walls of partisan prejudice. Dialogue and debate being replaced with name calling and assertion. Both sides having blind faith in a revealed truth, impervious to criticism and reinforced in echo chambers of the like minded. In consequence there is a popular dismissal of of all political debate and a pervasive cynicism where the views of all politicians are dismissed as self serving bunkum.

Whilst there certainly is a more aggressive debate in America, and a very clear divide between the two major parties, a universal condemnation of partisanship is misplaced. It leads to an exasperated response of, “a plague on both your houses”. At the extreme a view that there is no such thing as truth, or no such thing as truth other than what my side thinks. This is dangerous.

This needs to be resisted. In the current political debates within the United States there is no comparison between the position on fundamental issues between the Republicans and the Democrats. One is just more right than the other, by a lot.

No one has a monopoly on truth. However, that does not mean truth does not exist. Real distinctions can be made between right and wrong when the wrong in question is egregious. Similarly, between science and fanciful, self serving propaganda. If we reject this then we are allowing a world where “alternative facts” are real. Where debate is pointless as there is no way to arbitrate between what is personal preference and what is true.

It is not partisan to believe there are scientific truths that exist independent of my beliefs. Partly because there are people who devote their lives to something called the experimental method which in area after area has demonstrated the truth and effectiveness of this fundamental belief.

It is not partisan to believe climate change is real. Nor that man, through CO2e emissions, is affecting it. To believe thousands of scientists across the globe, in dozens of different disciplines all providing evidence pointing in one direction are part of a massive conspiracy is not partisan, it is stupid.

To believe that Covid-19 is a non-partisan killer because medical experts and epidemiologists say so, … oh, and also because there are a lot of dead people, is not partisan. It is common sense supported by science and should not compared in any way with the views of those who believe they will not catch the virus because they are immunised by the blood of Christ.

The first priority of a national leader is to protect their citizens. There are a host of ways in which this can be done. Suggesting it might make sense to ingest disinfectant is not one of them. That is not partisan thinking outside the box, it is not thinking. It betrays a lack of common sense, never mind scientific awareness, of breathtaking proportions.

Trump did not create the current pernicious divides in US politics. In truth they have been decades in the making. He is however their apotheosis. When you start down a road where you denigrate science in the interests of carbon extractive interests; where you try to tip the scales of justice in your favour by gaming the appointments system of justices; where you undermine the role of the state as a part of the problem not the solution; where you denigrate public service; where you use the law to persecute your opponents; where you blame foreigners for the problems besetting more and more of your fellow citizens, eventually you end up with a disaster like Trump.

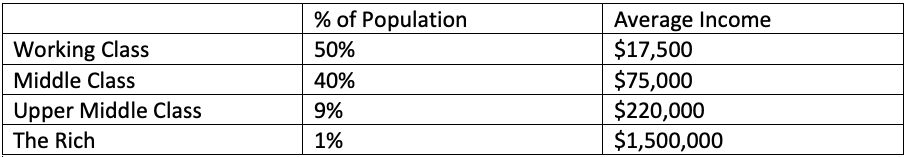

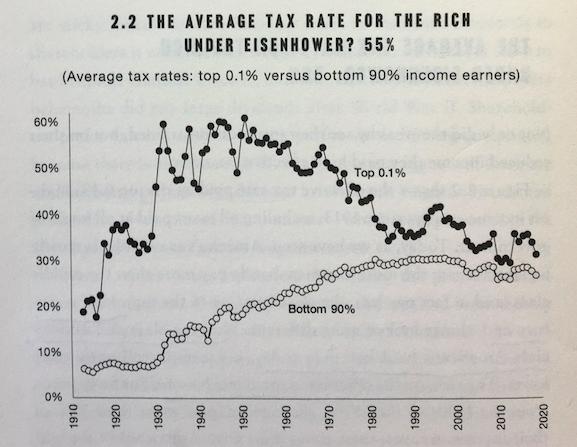

This is not the unfortunate outcome of a mutually destructive partisanship. It is a result of a conscious process funded by an ultra wealthy elite. An elite which is growing in confidence as to what it can get away with. One which avoids, an already regressive taxation system, and prioritises economic growth over peoples lives, without compunction.

We laugh too much at President Trump. His outrageous stupidity is his best defence. Challenging and opposing him is not partisan politics it is a life and death struggle for the future of American democracy. At the moment the Republican party in the US is just wrong and the States are paying an awful price for this.

Being a partisan is about being a strong supporter of a party or cause. It is not about surrendering your capacity for critical thought. The Democrats are partisan however when you compare what they are attempting to do on a whole range of issues their partisan proposals make sense. They are in no way equivalent to what the Republicans are defending if not supporting. The Republicans are wrong not because they are partisans. They are wrong because they are wrong.