If taxes buy civilisation you can understand President Trump’s lack of interest in paying them. However, it is an indictment of contemporary democracy that someone running for office can characterise tax avoidance as being “smart”. There is a pervasive problem about the attitude towards taxation in many western democracies. The vast bulk of the population seem to be resigned to the fact that for them they as inevitable as death but that somehow for the rich it is an optional sport.

There is a growing literature on this issue making clear the scale of the problem and the urgent need for reform. Reform which closes loopholes and ensures tax authorities have the support and resources they need. But also reforms which ensure income and wealth is effectively traced, not hidden away in secrecy regimes. And where progressive rates of tax are consistently levied on all forms of income.

One work which has looked at this problem in in detail in the United States is “The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make them Pay” by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zuckman. It provides an incisive overview of taxation policy and practice from the start of the 20th Century to the current day. Drawing on a century of tax data from a range of sources it analyses the total tax burden paid by groups from the very poorest up to the multi billionaires. It looks at Federal, local, sales and property taxes. It also includes payroll deductions for things like Medicare which are compulsory and effectively hypothecated taxes.

Using this data it outlines the levels of basic income inequality, how this was reduced by progressive income tax in the middle years of the 20th Century but how, since around 1980, that process has been reversed. It explores the role of secrecy jurisdictions or tax havens in undermining the taxation of corporations and high net worth individuals. It also looks at the industry of tax avoidance that has grown up, ironically as tax rates have come down.

The results are sobering. In the period since 1980 the amount of income captured by the top 1% in the US has grown spectacularly from 10% of national income to 20%. This is the result of two processes which interact. Firstly, differential salary increase rates where higher incomes increase at higher rates than lower incomes. Secondly, lower effective taxation rates on higher incomes.

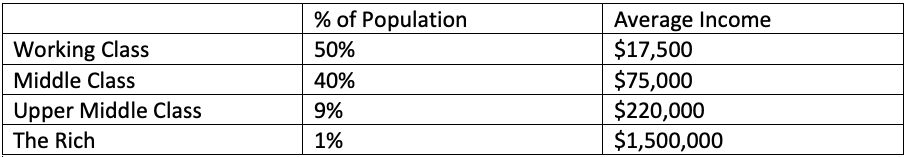

The results of this process are illustrated by Saed and Zuckman with a wealth of data. They begin by looking at the current distribution of incomes in the US. To obtain some kind of a base line they start with the nations GDP, make a couple of technical adjustments and divide the figure by the total adult population to get to an average $75,000 per adult. However, averages tend to hide at least as much as they reveal. So the next step is to look at how the income is distributed amongst various groups.

Four groups are identified: the working class or the bottom 50% of the adult population; the middle class, the next 40%; the upper middle class, the next 9%; and the rich, top 1%. Taking the figures for 2019 the average income for members of each of these groups was as shown in Table 1.

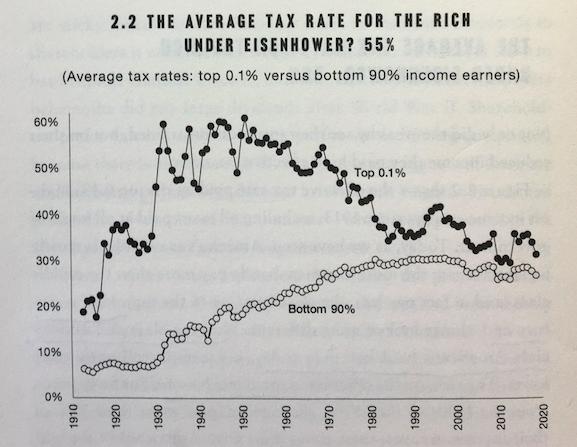

The second issue relates to the level of taxation applied to these various groups. What Saed and Zucman show is that over time this has come down, so that now the amount paid by those on the top 0.1% of incomes is very close to that paid by 90 % of the population. Indeed they show that the 400 highest earners in the US paid lower effective tax rates than the bottom 50% of earners.

The graph below, taken from their book, shows how effective taxation rates for the top 0.1% has evolved over the course of the 20th Century in comparison with that of the bottom 90%. There are three things to take away from this chart.  Firstly, at the start of the last century and through to the late 1970’s taxation was essentially progressive with the richest paying a rate at least twice as much as the vast bulk of the population. Secondly, from 1980 taxation rates became essentially flat. In other words the rate of taxation on fortunes and pittances were not that far apart. Third, from the start of the 1930’s through to the late 1970’s the average rates charged on the top 0.1% were high not just in comparison to the 90% but also high in absolute terms.

Firstly, at the start of the last century and through to the late 1970’s taxation was essentially progressive with the richest paying a rate at least twice as much as the vast bulk of the population. Secondly, from 1980 taxation rates became essentially flat. In other words the rate of taxation on fortunes and pittances were not that far apart. Third, from the start of the 1930’s through to the late 1970’s the average rates charged on the top 0.1% were high not just in comparison to the 90% but also high in absolute terms.

The high average rate which takes account of all taxes, some of which are regressive, was driven by some vey high progressive Federal rates. In 1944 the top marginal rate of the Federal income tax was 94% on incomes of $200,000 or more, equivalent to a salary today of £6m.

One of the key conclusions Saez and Zukman want to drive home is that rates of taxation are not cast in stone. It is not a case of ” ’twas ever thus.” Far from it. There were times when taxation rates were very high and when avoidance was minimal. The low levels of taxation on the rich are the result of conscious political decisions coming out of contested belief systems. They could be changed.

One of the arguments against change is that such high rewards are needed to ensure a growing economy and rising GDP. However the average growth rate for the period of high taxation and lower inequality was much better than that for the period since 1980 since when growth rates have slowed. Some will argue the two things are not necessarily connected. Happy to concede that but of course it means that high progressive taxation wont necessarily undermine growth going forward.

Saed and Zukman look at what can be done in a world where sovereign states compete with one another to tax corporations less and less, and where the absence of progressive taxation, amongst other things has allowed inequality in wealth to sky rocket. They address the need to treat all forms of income uniformly, so income from financial assets (the main source of income of the rich) is taxed at the same rate as income from employment. They explore a wealth tax and how this might work and they look at the scale of resources which could be brought into support public services that have been starved of resource for the past decade.

The timing of this book could not be better. Once Covid-19 is brought under control there will be an enormous bill to pay. That bill, like the bill for the Wars of the 20th Century needs to be shared in accordance with ability to pay. Expect much more debate about taxation in the coming years. Hopefully it will become clear that smart people pay taxes, and that smart rich people pay higher taxes than smart poor people. And the benefit of that is civilisation for all people.

The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make them Pay. Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman. WW Norton and Co. 2019.